It’s been about seven years since researchers used the CRISPR gene-editing system to reverse retinitis pigmentosa, a condition that causes blindness, in stem cells outside the body.

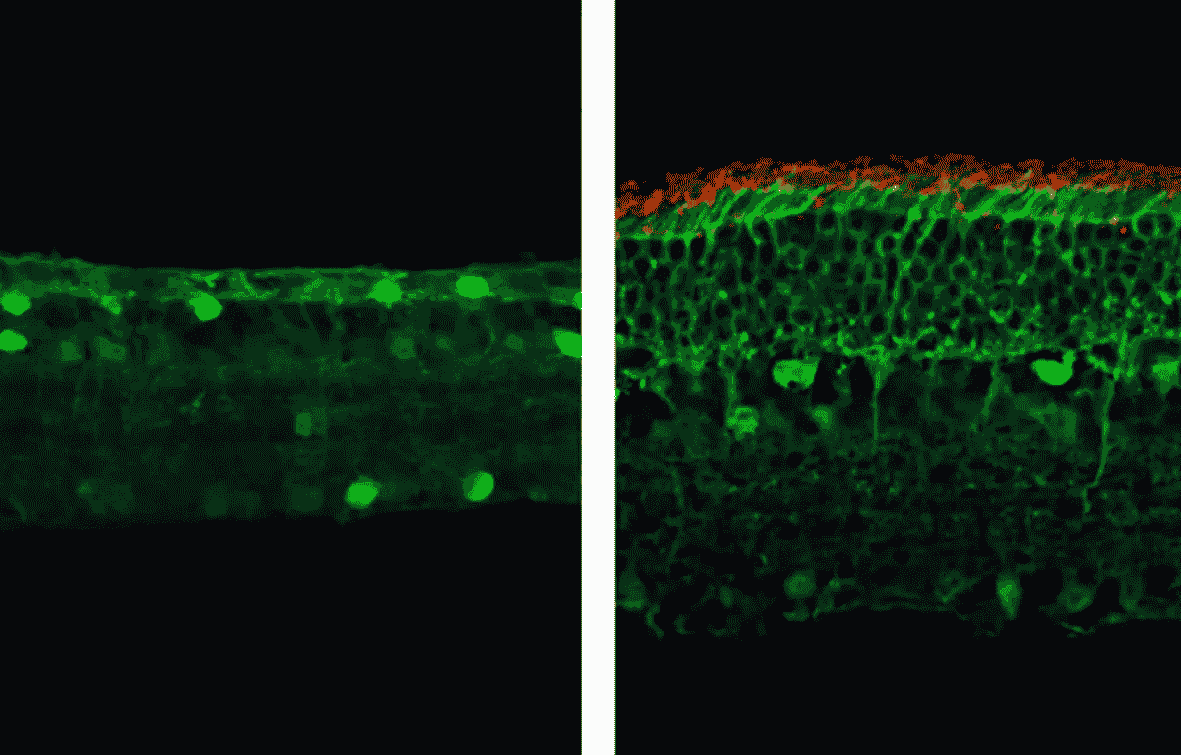

A different research team has now restored vision in a live animal model of the condition using a more refined version of CRISPR. The findings could pave the way for treatment for one in every 5,000 people who suffer from the condition.

How Gene Editing Works?

According to a study published today in the Journal of Experimental Medicine, researchers used gene editing to restore sight in mice with retinitis pigmentosa.

Using an enzyme called Cas9, scientists can precisely cut genes from DNA strands using the CRISPR process. After the genes have been cut, they can be altered, replaced, or deleted. The technology has been used for a variety of purposes, including reducing the flowering time of trees and fighting cancer. It has also previously been used to treat retinitis pigmentosa in rats by turning off mutated genes that cause photoreceptor loss in the eye.

Once the mutation was repaired, the gene resumed encoding the enzyme, preventing the death of rod and cone cells, which is how retinitis pigmentosa causes blindness. The mice regained their sight after the enzyme was properly produced again, as evidenced by head-turning tests and the successful completion of a visually guided water maze puzzle. The researchers confirmed that the animals’ restored vision lasted into old age.

Read more: 3 Patients test positive for Legionella at a Cincinnati hospital

What Is Retinitis Pigmentosa?

The techniques used by the researchers could be used to treat other genetic diseases in addition to retinitis pigmentosa.

The researchers stated that there is still much work to be done to establish human safety and efficacy for these types of surgeries. According to the National Eye Institute, retinitis pigmentosa refers to a group of disorders that cause progressive vision loss.

The loss of night vision is usually the first symptom. Tunnel vision can develop as the disease progresses. Photopsia – perceived flashes of light, loss of accurate color discrimination, and loss of visual acuity – can occur in the late stages.

The condition can also result in total vision loss. Most people, however, retain some light perception. People who develop the disease may have had visual disturbances, such as difficulty seeing in low-light situations. The visual field of most people gradually narrows over time.

Some people may find driving at night difficult because they struggle to transition from the bright light of oncoming headlights to the darkness of the night.

Read more: What happens to your body if you do not drink water during the day?