Jean Heller was working hard on the floor of the Miami Beach Convention Center when a coworker from the opposite end of the country who worked for the Associated Press entered her workspace behind the event stage and handed her a thin envelope made of manila paper.

Edith Lederer told the 29-year-old Heller, “I’m not an investigative reporter,” as competitors typed away beyond the thick grey hangings that separated news outlets covering the 1972 Democratic National Convention.

Lederer was one of the reporters covering the event. “However, I can’t help but feel like there’s something more to this.”

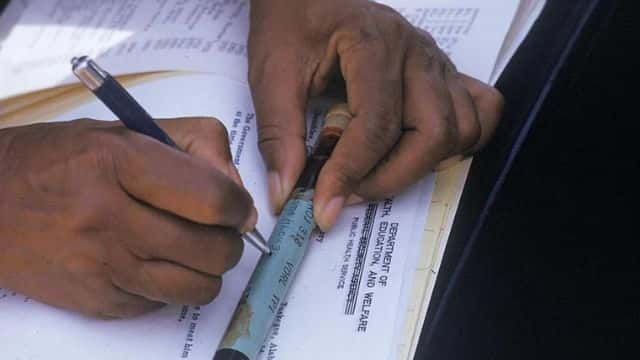

Inside were documented that told a story that, even today, boggles the mind: For four decades, the United States government had denied hundreds of poor Black men treatment for syphilis so that researchers could study the effects of the disease on the human body.

This was done to study the ravages of the disease.

It was known as “The Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male” when it was conducted by the United States Public Health Service.

One of the largest medical scandals in the history of the United States, the Tuskegee Study is an atrocity that continues to fuel mistrust of the government and health care among African-Americans.

The name “Tuskegee Study” would soon become the only name that was used to refer to it.

When Heller thinks back to that moment, which occurred fifty years ago, he says, “I thought, ‘It couldn’t be.'” “The awfulness of this situation.”

The events that led to the discovery of the study started four years earlier, at a party that was held in San Francisco.

In 1968, Lederer was working at the Associated Press bureau in that city when she ran into Peter Buxton. Buxton had taken a job at the local Public Health Service office in 1965 when he was still in the process of completing his graduate studies in history.

His responsibilities included keeping track of cases of venereal disease in the Bay Area.

In the year 1966, Buxton had overheard colleagues discussing a syphilis research project that was being conducted in Alabama.

He dialled the number for what is now known as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and inquired as to whether or not they had any documents that they could make available.

According to what he revealed to The American Scholar magazine for a story that was published in 2017, he was given a manila envelope that contained 10 reports.

According to him, he had an immediate realization that the study was conducted in a manner that was contrary to ethical standards, and he informed his superiors of this fact not once but twice in reports. Taking care of your own work, and stopping worrying about Tuskegee, was the essence of the response.

In the end, he decided to leave the agency, but he was unable to leave Tuskegee.

Therefore, Buxton went to consult his journalist friend “Edie,” who declined the offer.

During a recent interview, Lederer stated, “I knew that I could not do this.”The Associated Press, in 1972, was not going to send a young reporter from San Francisco to Tuskegee, Alabama, for them to conduct an investigation for a story.

However, she lied to Buxton and said that she knew someone who could help.

Heller was one of the few women working in the field at the time she joined the AP’s Special Assignment Team, which was still in its infancy.

Nevertheless, she did not escape the casual sexism that pervaded the period.

In a story about the team that was published in 1968 in AP World, the employee newsletter for the wire service, the squad was described as “10 men and one cute gal.”

The “pixie-like” reporter, who stood only 5 feet 2 inches tall, was described as “lovely and competent” in the caption that accompanied her photo.

Lederer had worked with Heller back when they were both at the New York headquarters of the Associated Press (AP), which was then located at 50 Rockefeller Plaza. Heller had begun his career working at the radio desk there.

Lederer says, “I had no doubt that she was an outstanding journalist.”

Lederer made a brief detour to Miami Beach on her way to see her parents in Florida.

There, Heller was working as part of a team covering the convention, which ultimately resulted in the election of U.S. Senators George McGovern of South Dakota and Thomas Eagleton of Missouri as the Democratic presidential and vice presidential nominees. Lederer visited Miami Beach during her trip to see her parents in Florida.

During a recent interview that took place at her residence in North Carolina, Heller recalled placing the hacked documents from the PHS in her briefcase.

She claims that she didn’t get around to reading the contents of the letter until they were airborne heading back to Washington.

Ray Stephens, the head of the investigative team, was seated next to her at the table. She presented the documents to him for review.

Stephens came to the realization that the government was not denying the existence of the study; rather, they were simply refusing to talk about it.

Heller remembers Stephens telling him, “When we get back to Washington, I want you to drop everything else you’re doing and focus on this.” Stephens was referring to the situation in Washington.

She was met with resistance from the government, which declined to discuss the study. Therefore, Heller began his tour in other locations, beginning with educational institutions such as colleges, universities, and medical schools.

She went so far as to contact the gynaecologist that her mother had seen; he was described as a “direct down the line, middle of the road, superior doctor.”

“When I asked him if he was aware of this, he said, ‘No, that’s not happening.'” I just don’t believe it.'”

Last but not least, she mentioned that one of her sources recalled reading about the syphilis study in a relatively obscure medical journal. She was planning on visiting the public library in Washington, DC.

“I asked them if they had any kind of documents, books, magazines, or whatever… that would fit a, what today we would call a profile or a search engine search, for ‘Tuskegee,’ ‘farmers,’ ‘Public Health Service,’ and syphilis,'” Heller says. “They said they didn’t have anything that would fit that description.”

They discovered an obscure medical journal that had been chronicling the study’s “progress,” but Heller is unable to recall the title of the publication.

She explains, “Every couple of years, they would write something about it.” “Every couple of years,” she says. “The findings took up the majority of the discussion, while the ethics of the experiment were never brought up.”

She says in a hushed tone, “I knew that people had died, and I was about to tell the world who they were and what they had.” “I was about to tell the world who they were and what they had.” It would not have been proper for you to have taken any pleasure in that situation.

Heller then made his way back to the PHS, this time armed with the journal. They surrendered.

“As the bureau chief, Marv Arrowsmith, walked by my desk, I greeted him with a “Hey, Marv. Will you publish this?'” she recollects asking him at the time. Then he looked at me and asked, ‘Can you prove it?’ after he had finished reading it. I said, ‘Yes.’ He responded by telling me, “You got it.”

Read more:-

- DA Orleans The second week of the federal tax fraud trial for Jason Williams begins with IRS agents’ evidence.

- The Internal Revenue Service is not living up to the expectations of its mission.

- Editorial Boards of Newspapers Criticized Donald Trump for Being “Unworthy” and Saying That He “Utterly Failed” on January 6.

Arrowsmith suggested that they present the story to the now-defunct Washington Star first, with the condition that it be published on the front page if the Star agreed to do so.

“The Star was a highly respected PM newspaper, and if they took it seriously, others might follow,” says Heller. “If they took it seriously, others might follow.”

The article was published on the 25th of July, 1972, which was a Tuesday. It was a terrifying account to hear.

In 1932, the Public Health Service, in collaboration with the illustrious Tuskegee Institute, began recruiting African-American men in the county of Macon, located in the state of Alabama.

The researchers told them that they needed to be treated for “bad blood,” which is a catch-all term used to describe a variety of diseases and conditions, such as anaemia, fatigue, and syphilis. The treatment available at the time caused