In the days leading up to Hurricane Helene, Dr. Lisa Kaufmann worked around the clock to ensure her North Carolina hospital system was fully prepared, storing supplies such as water, food, medication, and equipment.

However, over a week after the storm’s fierce floodwaters devastated much of the state’s western region, Kaufmann, the chief medical officer for UNC Appalachian Regional Healthcare System’s three hospitals, said they are now dealing with another problem. Forty-two hospital staff are still missing, unable to be reached by phone, and perhaps trapped in inaccessible areas.

“We think most of them are probably OK,” Kaufmann added. “They just have no communication, but we don’t know, so it is very stressful for everybody working here in any capacity.” While many healthcare personnel are accustomed to stress, many in the disaster zone say their new circumstances exacerbate it.

Hannah Drummond, a registered nurse at Mission Health in Asheville and the lead representative for National Nurses United, the union representing the nurses there, described it as an emotional roller coaster. “There are moments that we have where we’re able to cope and compartmentalize and focus on the patient, and there were moments where somehow we’ve been able to joke and laugh, and then there are other moments where we’re hugging each other, choking back our tears,” Drummond recounted. She said seeing her colleagues come together and help one another has been encouraging, but with her hometown decimated and friends still missing, it’s taking an emotional toll.

“We still have coworkers we haven’t heard from,” Drummond added. “With the patient load finally dying, people are going out to their addresses because we haven’t been able to get a hold of them to check and see if they’re OK.” “It’s just like, do you not have cell service, or are you dead?” She added. Only nine High Country Community Health’s 13 clinics are operational following the storm. According to Alice Salthouse, the clinics’ founder and CEO, they could first not contact several staff members.

“It was sickening,” Salthouse explained. “It’s as if you have coworkers with whom you spend roughly the same time as your family. And we work together. We are a team, and there was a lot of concern.” After four days of constant calls and texts, they were relieved and overjoyed when they finally reached out to all 220 employees. “We just whenever we would say, ‘Oh, we got a hold of Vicky,’ and everybody would do a high five and virtually do cartwheels,” Salthouse recalled.”

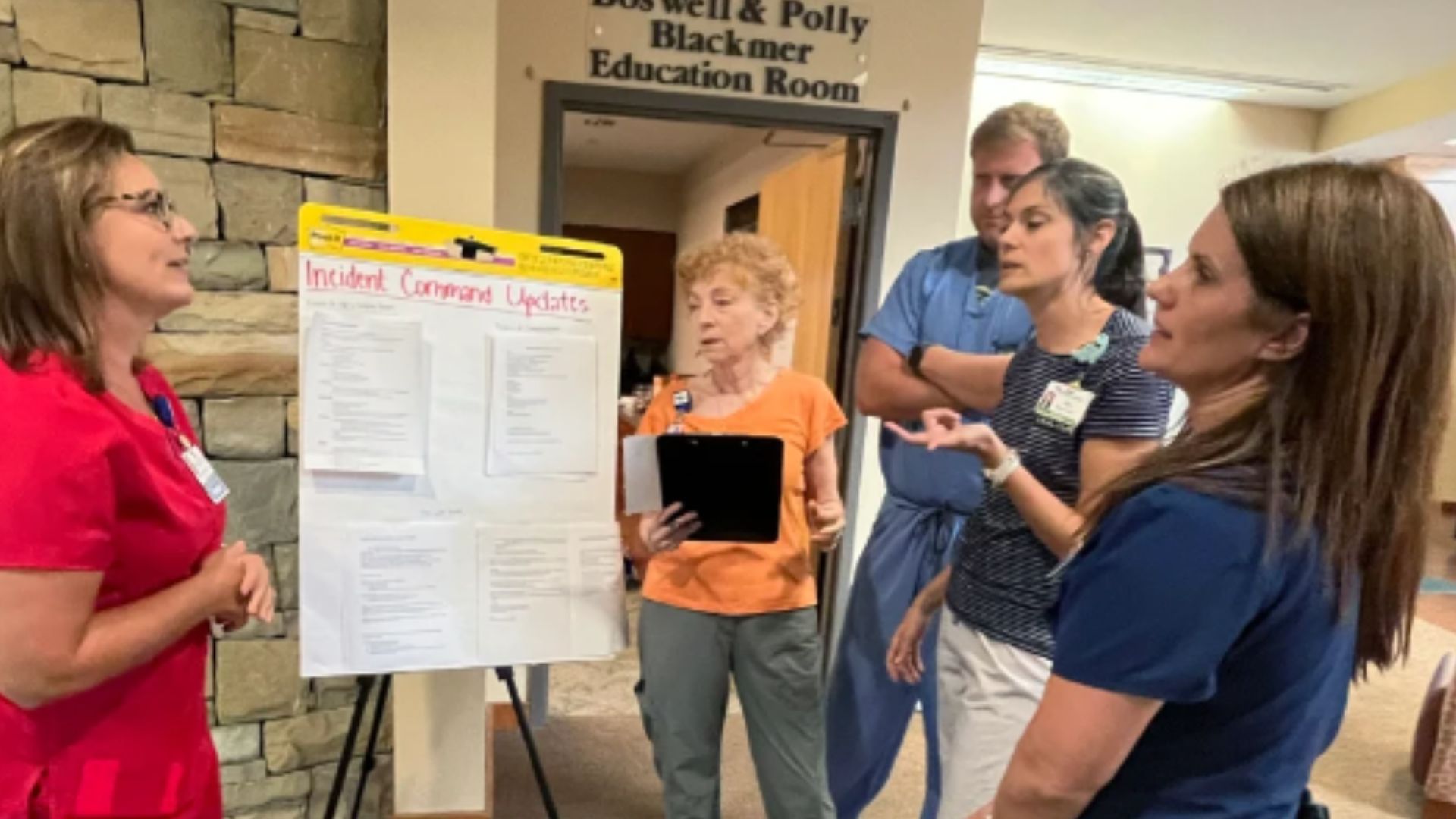

According to Kaufmann, the number of unaccounted-for personnel at UNC Appalachian was far higher immediately following the hurricane. She stated over half of the 1,600 staff were unreachable. So she got inventive, persuading the marketing team to utilize social media to request that all staff check in and let them know if they were safe. “That number started exploding with calls from employees who were trying to call in because they wanted people to know, ‘I’m OK’ and ‘This is my status on whether I can get through to report to work’ and so forth,” said Kaufmann.

But as the days pass and hundreds of people remain missing, Kaufmann said she’s keeping hopeful and directing her frustration and concern toward figuring out how to find them. “People are reaching out to people if they know someone who is a neighbor,” according to her. “The search-and-rescue people also have names of people known to be not included, and as they are sweeping the counties, house by house, they’re making their way through the jungle of fallen trees to check on everybody.”